Wolfman Jack

Wolfman Jack | |

|---|---|

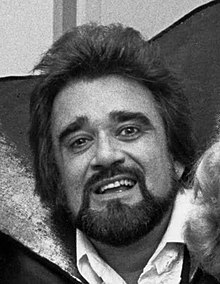

Jack in 1979 | |

| Born | Robert Weston Smith January 21, 1938 Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 1995 (aged 57) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1960–1995 |

| Spouse | Lucy "Lou" Lamb |

| Children | 2 |

Robert Weston Smith (January 21, 1938 – July 1, 1995), known as Wolfman Jack, was an American disc jockey active for over three decades.[1] Famous for the gravelly voice which he credited for his success, saying, "It's kept meat and potatoes on the table for years for Wolfman and Wolfwoman. A couple of shots of whiskey helps it. I've got that nice raspy sound."[2]

Early life

[edit]Smith was born in Brooklyn, New York City, on January 21, 1938, the younger of two children of Anson Weston Smith, an Episcopal Sunday school teacher, writer, editor, and executive vice president of Financial World, and his wife, Rosamond Small. He lived on 12th Street and 4th Avenue and went to Manual Training High School in the Park Slope section. His parents divorced while he was a child. To help keep him out of trouble, his father bought him a large Trans-Oceanic radio, and Smith became an avid fan of R&B music and the disc jockeys who played it, including Douglas "Jocko" Henderson of Philadelphia; New York's "Dr. Jive" (Tommy Smalls); the "Moon Dog" from Cleveland, Alan Freed; and Nashville's "John R." Richbourg, who later became his mentor. After selling encyclopedias and Fuller brushes door-to-door, Smith attended the National Academy of Broadcasting in Washington, D.C.[3]

Broadcasting career

[edit]After graduating from NAB in 1960, Smith began working as "Daddy Jules" at WYOU in Newport News, Virginia. When the station format changed to "beautiful music", he became known as "Roger Gordon and Music in Good Taste". In 1962, Smith moved to country music station KCIJ/1050 in Shreveport, Louisiana, as the station manager and morning disc jockey, "Big Smith with the Records". He married Lucy "Lou" Lamb in 1961, and they had two children.[4]

Cleveland's Alan Freed had originally called himself the "Moon Dog" after New York City street musician Moondog. Freed both adopted this name and used a recorded howl to give his early broadcasts a unique character. Smith's adaptation of the Moondog theme was to call himself Wolfman Jack and add his own sound effects. The character was based in part on the manner and style of bluesman Howlin' Wolf. At KCIJ, he first began to develop his famous alter ego, Wolfman Jack. According to author Philip A. Lieberman, Smith's "Wolfman" persona "derived from Smith's love of horror films and his shenanigans as a 'wolfman' with his two young nephews. The 'Jack' nickname was taken from the 'hipster' lingo of the 1950s, as in 'Take a page from my book, Jack', or the more popular, 'Hit the road, Jack.'"[5]

In 1963, Smith took his act to the border when Inter-American Radio Advertising's Ramon Bosquez hired him and sent him to the studio and transmitter site of XERF-AM at Ciudad Acuña in Mexico, a station across the U.S.-Mexico border from Del Rio, Texas, whose high-powered border blaster signal could be picked up across much of the United States. In an interview with writer Tom Miller, Smith described the reach of the XERF signal: "We had the most powerful signal in North America. Birds dropped dead when they flew too close to the tower. A car driving from New York to L.A. would never lose the station."[6]

Many of the Mexican border stations broadcast at 150,000 watts, three times the U.S. limit, meaning that their signals were picked up all over North America, and at night as far away as Europe and the Soviet Union. At XERF, Smith developed his signature style (with phrases such as, "Who's this on the Wolfman telephone?") and widespread fame. The border stations made money by renting time to Pentecostal preachers and psychics, and by taking 50% of the profit from anything sold by mail order. The Wolfman did pitches for dog food, weight-loss pills, weight-gain pills, rose bushes, and baby chicks. Even a pill called Florex, which was supposed to enhance one's sex drive, was sold. "Some zing for your ling nuts", the Wolfman would say.[7]

XERB was the original call sign for the border blaster station in Rosarito Beach, Mexico, which was branded as The Mighty 1090 in Hollywood, California. The station boasted "50,000 watts of Boss Soul Power". That station continues to broadcast under the call sign XEPRS-AM. XERB also had an office in the rear of a small strip mall on Third Avenue in Chula Vista, California just 10 minutes from the Tijuana–San Diego border crossing. The Wolfman was rumored to actually broadcast from this location during the early to mid-1960s. Smith left Mexico after eight months and moved to Minneapolis to run station KUXL. Although Smith was managing a Minneapolis radio station, he was still broadcasting as Wolfman Jack on XERF via taped shows that he sent to the station.

Missing the excitement, however, Wolfman returned to border radio to run XERB, and opened an office on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles in January 1966. He recorded his shows in Los Angeles and shipped his tapes across the border into Mexico, where they would then be beamed across the U.S.[8]

In 1971, the Mexican government, under pressure from the Roman Catholic church, banned the Pentecostal preachers from the radio, taking away 80% of XERB's revenue. Smith then moved to station KDAY 1580 in Los Angeles, which could only pay him a fraction of his former XERB income. Smith capitalized on his fame, though, by editing his old XERB tapes and selling them to radio stations everywhere, becoming one of the first rock-and-roll syndicated programs (as the tapes began to age, they were eventually marketed to oldies stations). He also appeared on Armed Forces Radio from 1970 to 1986. At his peak, Wolfman Jack was heard on more than 2,000 radio stations in 53 countries.[9] He was heard as far afield as the Wild Coast, Transkei, on Capital Radio 604 based there.[10]

In a deal promoted by Don Kelley, the Wolfman was paid handsomely to join WNBC in New York in August 1973, the same month that American Graffiti premiered, and the station did a huge advertising campaign in local newspapers predicting the Wolfman would propel their ratings over those of their main competitor, WABC's Cousin Brucie (Bruce Morrow). The advertisements proclaimed, "Cousin Brucie's Days Are Numbered / Wolfman Jack Is on the Prowl", and thousands of small, tombstone-shaped paperweights were distributed that said, "Cousin Brucie is going to be buried by Wolfman Jack".[11][12]

After less than a year, WNBC hired Cousin Brucie, and Wolfman Jack went back to California to concentrate on his syndicated radio show, which was carried on KRLA-Pasadena (Los Angeles) from 1984 to 1987. He moved to Belvidere, North Carolina, in 1989, to be closer to his extended family.[13] In the 1980s, he did a brief stint at XEROK 80, another border-blaster station that was leased by Dallas investors Robert Hanna, Grady Sanders, and John Ryman. He also hosted a TV show at Little Darlin's Rock n' Roll Palace, which was eventually renamed Wolfman Jack's Rock'n'Roll Palace.[14] Ryman then moved Smith to Scott Ginsburg-owned Y95 in Dallas, Texas.

Recordings of Wolfman Jack's old shows were reintroduced to syndication a decade after his death and remain available to local stations, through Talent Farm as of mid-2020.[15] In 2024, as part of a oldies format marking its 85th anniversary, XEPRS began to carry the remastered recordings.[16][17]

Film, television, and music career

[edit]In his early days, Wolfman Jack made sporadic public appearances, usually as a master of ceremonies for rock bands at Los Angeles clubs. At each appearance, he looked a little different because he had not decided what the Wolfman should look like. Early pictures show him with a goatee, but sometimes he combed his straight hair forward and added dark makeup to look somewhat "ethnic." Other times he had a big afro wig and large sunglasses. The ambiguity of his race contributed to the controversy of his program. His audience finally got a good look at him when he appeared in the 1969 film A Session with the Committee, a montage of skits by the comedy troupe The Committee.

Wolfman Jack started his recording career in Minneapolis while working at KUXL Radio in 1965 with George Garrett, who helped record the album Boogie with the Wolfman by Wolfman Jack and the Wolfpack on the Bread Label. He was also responsible for engineering, producing, and assembling the band.[18] Wolfman Jack also released Wolfman Jack (1972) and Through the Ages (1973) on the Wooden Nickel label.[19]

In 1973, he appeared as himself in George Lucas's second feature film American Graffiti. Lucas gave him a fraction of a "point", the division of the profits from a film, and the extreme financial success of American Graffiti provided him with a regular income for life. He also appeared in the film's 1979 sequel More American Graffiti, though only through voice-overs. In 1978, he appeared as Bob "The Jackal" Smith in a made-for-TV movie Deadman's Curve based on the musical careers of Jan Berry and Dean Torrence of Jan and Dean. Smith appeared in several television shows as Wolfman Jack, including The Odd Couple, What's Happening!!, Vega$, Hollywood Squares, Married... with Children (his final public performance), Emergency!, The New Adventures of Wonder Woman, and Galactica 1980. He was the regular announcer and occasional host for The Midnight Special on NBC from 1973 to 1981. He was the host of his variety series The Wolfman Jack Show, which was produced in Canada by CBC Television in 1976 and syndicated to stations in the U.S. In 1984, Wolfman Jack starred as himself on the short-lived ABC animated series Wolf Rock TV. He also voiced the chief of the Rama Lama tribe on the TV special Garfield in Paradise in 1986.

Jim Morrison's lyrics for "The WASP (Texas Radio and the Big Beat)" were influenced by Wolfman Jack's broadcasting. His characteristic voice is imitated by disc jockey Ken Griffin on Sugarloaf's 1974 hit single "Don't Call Us, We'll Call You" and he is mentioned on the Grateful Dead song "Ramble On Rose".[20] He furnished his voice in The Guess Who's top-10 hit single "Clap for the Wolfman". In 1976, he furnished his voice on "Did You Boogie (With Your Baby)" by Flash Cadillac & the Continental Kids. Wolfman Jack was regularly parodied on The Hilarious House of Frightenstein as "The Wolfman," an actual werewolf disc jockey with a look inspired by the original The Wolf Man movies. A few years earlier, Todd Rundgren recorded the tribute "Wolfman Jack" on the album Something/Anything?; the single version of the track includes a shouted talk-over introduction by the Wolfman, but on the album version, Rundgren performs that part himself. Canadian band The Stampeders also released a cover of "Hit the Road Jack" in 1975 featuring Wolfman Jack. From 1975 to 1980, Wolfman Jack hosted Halloween Haunt at Knott's Berry Farm, which transforms itself into Knott's Scary Farm each year for Halloween. It was the most successful special event of any theme park in the country, and often sold out.[21][22][23]

In 2012, the estate of Wolfman Jack released a hip-hop single featuring Wolfman Jack clips as the vocals.[24] In 2016, clips from the Wolfman Jack Radio Program were used in the Rob Zombie film 31.[25]

Radio Caroline

[edit]When the one surviving ship in what had originally been a pirate radio network of Radio Caroline North and Radio Caroline South sank in 1980, a search began to find a replacement. Because of new laws passed in the UK in 1967 (Marine, &c., Broadcasting (Offences) Act 1967), the sales operation needed to be situated outside of the UK. For a time, Don Kelley, Wolfman Jack's business partner and personal manager, acted as the West Coast agent for the planned new Radio Caroline, but the deal eventually fell apart.

As a part of this process, Wolfman Jack was set to deliver the morning shows on the new station. To that end, he recorded a number of programs that never aired, because the station did not come on air according to schedule. (It eventually returned in 1983 from a new ship, which remained at sea until 1990.) Today, those tapes are traded among collectors of his work.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]On July 1, 1995, Smith died from a heart attack at his house in Belvidere, North Carolina, shortly after finishing a weekly broadcast. He was 57 years old.[2][26] He is buried at a family cemetery in Belvidere.[27]

Legacy and portrayals

[edit]Clap for the Wolfman is a song written by Burton Cummings, Bill Wallace, and Kurt Winter performed by their band, the Guess Who. The song appeared on their 1974 album, Road Food. The song was ranked #84 on Billboard magazine's Top Hot 100 songs of 1974.[3]

- Wolfman Jack made a guest vocal appearance on 2 songs (" Tighten Up " & " Nice Age ") from Yellow Magic Orchestra: X00 Multiplies 1980 album.

- Wolfman Jack is portrayed by Jack Black in the 2022 satirical biopic Weird: The Al Yankovic Story. He is portrayed as a rival of Dr. Demento (played in the film by Rainn Wilson).

- From 1978 to 1980, an animatronic band called the Wolf Pack 5 appeared twice at the IAAPA and at the first Showbiz Pizza. The leader of the band was an anthropomorphic wolf who was modeled after Jack. He's voiced by Aaron Fechter.[citation needed]

- On Diamond D's 1992 album Stunts, Blunts and Hip Hop, a parody of Wolfman Jack is done on the skit "Wuffman Stressed Out".

- Wolfman Jack's voice was used in the 1989 beat 'em up arcade video game DJ Boy as the announcer Demon Kogure in the American version.

- Wolfman Jack is sampled on J-Dilla's 2006 album, Donuts, on the track "Anti-American Graffiti". The sample comes from the 1973 album, How Time Flys by David Ossman.

- In his 2020 song "Murder Most Foul," Bob Dylan invokes Wolfman Jack many times.[28]

- Wolfman Jack appeared at the Modesto American Graffiti Festival several times, for the first time in 1988. The film American Graffiti, which portrays Wolfman Jack, takes place in Modesto, California.[29]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | The Seven Minutes | Himself | |

| 1973 | American Graffiti | Disc Jockey / Himself | |

| 1973 | The Odd Couple | Himself | "The Songwriter" |

| 1975 | Emergency! | Disc Jockey | "The Inspection" |

| 1978 | Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band | Our Guests At Heartland | |

| 1978 | Hanging on a Star | Gordon Shep | |

| 1978 | Deadman's Curve | Bob "The Jackal" Smith | |

| 1978 | The New Adventures of Wonder Woman | Infra Red | "Disco Devil" |

| 1978 | What's Happening!! | Himself | "Going, Going, Gong" |

| 1979 | More American Graffiti | Himself | |

| 1980 | Motel Hell | Reverend Billy | |

| 1980 | The Fonz and the Happy Days Gang | Narrator | Animated |

| 1980 | Galactica 1980 | Himself | "The Night the Cylons Landed" |

| 1984 | Wolf Rock TV | Himself | |

| 1985 | The Midnight Hour | Radio DJ | Made-for-television movie |

| 1986 | Garfield in Paradise | Rama Lama Tribe Chief (voice) | Animated TV special |

| 1988 | Mortuary Academy | Bernie Berkowitz | |

| 1989 | Midnight | Himself | |

| 1992 | Swamp Thing | Hurly | "Children of the Fool" |

| 1995 | Married... with Children | Himself | "Ship Happens: Part 1" (Final appearance) |

References

[edit]- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (July 2, 1995). "Wolfman Jack, Raspy Voice Of the Radio, Is Dead at 57". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bob Pinheiro (July 1, 1995). "Wolfman Jack, pioneer disc jockey dies at 57". Modestoradiomuseum.org. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ "Family tree of WOLFMAN JACK". Geneanet. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ John A. Drobnicki, "Wolfman Jack (Robert Weston Smith)", in The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, Vol. 4 (Scribner's, 2001), p. 581.

- ^ Philip A. Lieberman, Radio's Morning Show Personalities: Early Hour Broadcasters and Deejays from the 1920s to the 1990s (McFarland & Company, 1996), p. 58.

- ^ Tom Miller. On the Border: Portraits of America's Southwestern Frontier, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Wes Smith, The Pied Pipers of Rock 'n' Roll (Longstreet Press, 1989), p. 272.

- ^ Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford, Border Radio (Limelight Editions, 1990).

- ^ John A. Drobnicki, "Wolfman Jack (Robert Weston Smith)". in The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives, Vol. 4 (Scribner's, 2001), p. 582.

- ^ "Wolfman Jack in Africa, 1980. Borderblasting in a Bantustan". July 16, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ Ben Fong-Torres, The Hits Just Keep on Coming: The History of Top 40 Radio (Miller Freeman Books, 1998), p. 142.

- ^ Paul Levinson (July 4, 1976). "Wolfman Hits the Road, Jack". The Village Voice. p. 34.

- ^ James F. Mills, "Wolfman Turns into Country Gentleman: N.C. Mansion Home to Rock 'n' Roll DJ", Charlotte Observer (February 27, 1994), p. 8B.

- ^ "Wolfman and 'Midnight': Nostalgia but No Regrets". Los Angeles Times. May 21, 1988. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "The Talent Farm Adds the Wolfman Jack Show". radioinsight.com. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ "Wolfman Jack Is Back On A Baja California Border Blaster". Radio Ink. November 5, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ "There's a radio station bringing '50s through '70s oldies to Southern California". Daily News. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ Minnesota Rocked, Tom Tourville, 2nd Edition, 1983, LCCN 82-74566

- ^ Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (October 26, 2005). "Wooden Nickel Album Discography". Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ^ "The Annotated "Ramble On Rose"". Artsites.ucsc.edu. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Merritt, Christopher, and Lynxwiler, J. Eric. Knott's Preserved: From Boysenberry to Theme Park, the History of Knott's Berry Farm, pp. 126–29, Angel City Press, Santa Monica, CA, 2010. ISBN 978-1-883318-97-0.

- ^ "Scary Farm". Ultimatehaunt.com. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ "Knott's In Print: Halloween Haunt in the Beginning". Knottsinprint.blogspot.com. October 24, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Wolfman Jack – Topic (October 11, 2015). "Lay Your Hand On the Radio". Retrieved September 11, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "'31' Review: Rob Zombie Makes Sickest Film Yet, Also His Most Fun". September 2, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "A short synapses about Wolfman Jack, his accomplishments, and his life". Archived from the original on July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Kin Plan Park, Museum in Honor of Wolfman Jack". Deseret News. November 12, 1995. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ "Murder Most Foul | The Official Bob Dylan Site". www.bobdylan.com. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ "Test Your Knowledge of Graffiti History". The Modesto Bee. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

External links

[edit]- "New Year's Eve, 1993, With Wolfman Jack !" Archived June 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Wolfman Jack: The Mouth Heard 'Round the World (interview)

- Kip Pullman's American Graffiti Blog

- Wolfman Jack and the gun battle in the Mexican desert

- What made Wolfman Jack great?

- Wolfman Jack at IMDb

- Wolfman Jack discography at Discogs

- Wolfman Jack at Find a Grave